How and why four cardinal forms of organization — tribes, hierarchical institutions, markets, and networks (TIMN) — explain social evolution. How and why space-time-action cognitions (STA:C) explain people’s mindsets.

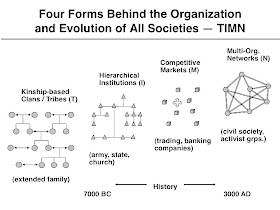

According to my review of history and theory, four forms of organization — and evidently only four — lie behind the governance and evolution of all societies across the ages:

- The tribal form was the first to emerge and mature, beginning thousands of years ago. Its main dynamic is kinship, which gives people a distinct sense of identity and belonging — the basic elements of culture, as manifested still today in matters ranging from nationalism to fan clubs.

- The institutional form was the second to emerge. Emphasizing hierarchy, it led to the development of the state and the military, as epitomized initially by the Roman Empire, not to mention the Catholic papacy and other corporate enterprises.

- The market form, the third form of organization to take hold, enables people to excel at openly competitive, free, and fair economic exchanges. Although present in ancient times, it did not gain sway until the 19th century, at first mainly in England.

- The network form, the fourth to mature, serves to connect dispersed groups and individuals so that they may coordinate and act conjointly. Enabled by the digital information-technology revolution, this form is only now coming into its own, so far strengthening civil society more than other realms.

The development of each form has a long history. Early versions of all four were present in ancient times. But as deliberate, formal systems with philosophical portent, each has gained strength at a different rate and matured in a different epoch over the past 10,000 years. Tribes developed first (in the Neolithic era), hierarchical institutions next (notably, with the Roman Empire and then the absolutist states of the 16th century), and competitive markets later (as in England and the United States in the 18th century). Now, collaborative networks are on the rise as the next great form. Its cutting edge currently lies among activist nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) associated with civil society. See Slide 1.

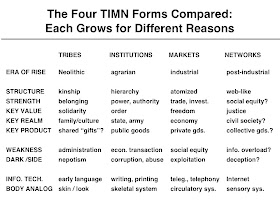

The four forms compared

Each of the four forms, writ large, embodies a distinctive set of structures, processes, beliefs, and dynamics about how society should be organized — about who gets to achieve what, why, and how. Each involves different codes and standards about how people should treat each other. Each enables people to do something — to address some social problem — better than they could by using another form. Each attracts and energizes different kinds of actors and adherents. Each has different ideational and material bases. Each has both bright and dark sides, both strengths and weaknesses. And each can be gotten “right” or “wrong” in various ways, depending on circumstances.

Once a form is subscribed to by many actors, it becomes more than a mere form: It develops into a realm, even a system, of thought and behavior. Indeed, the rise of each form spells an ideational and structural revolution. Each is a generator of order, because each defines a set of interactions (or, transactions) that are attractive, powerful, and useful enough to create a distinct realm of activity, or at least its core. Each becomes the basis for a governance system that is self-regulating and, ultimately, self-limiting. And each tends to foster a different kind of worldview, for each orients people differently toward social space, time, and action. What is deemed rational — how a “rational actor” should behave — is different for each form; no single “utility function” suits them all.

Each form becomes associated with high ideals as well as new capabilities. Yet, all the forms are ethically neutral — as neutral as technologies — in that they have both bright and dark sides and can be used for good or ill. The tribal form, which should foster communal solidarity and mutual caring, may also breed a narrow, bitter clannishness that can justify anything from nepotism to murder in order to shield and strengthen a clan and its leaders. The hierarchical institutional form, which should lead to professional rule and regulation, may also be used to uphold corrupt, arbitrary dictators. The market form, which should bring free, fair, open exchanges, may also be distorted and rigged to allow unbridled piracy, speculation, and profiteering. And the network form, which can empower civil society actors to serve public interests, may also be used to strengthen “uncivil society” — say, by enabling terrorist groups and crime syndicates. So, it is not just the bright sides of each form that foster new values and actors; their dark sides may do so as well. See Slide 2.